- Home

- Pam Jenoff

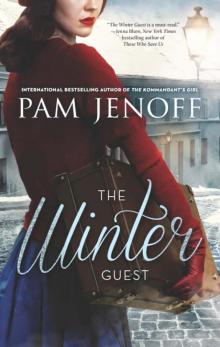

The Winter Guest

The Winter Guest Read online

A stirring novel of first love in a time of war and the unbearable choices that could tear sisters apart, from the celebrated author of The Kommandant’s Girl

Life is a constant struggle for the eighteen-year-old Nowak twins as they raise their three younger siblings in rural Poland under the shadow of the Nazi occupation. The constant threat of arrest has made everyone in their village a spy, and turned neighbor against neighbor. Though rugged, independent Helena and pretty, gentle Ruth couldn’t be more different, they are staunch allies in protecting their family from the threats the war brings closer to their doorstep with each passing day.

Then Helena discovers an American paratrooper stranded outside their small mountain village, wounded, but alive. Risking the safety of herself and her family, she hides Sam—a Jew—but Helena’s concern for the American grows into something much deeper. Defying the perils that render a future together all but impossible, Sam and Helena make plans for the family to flee. But Helena is forced to contend with the jealousy her choices have sparked in Ruth, culminating in a singular act of betrayal that endangers them all—and setting in motion a chain of events that will reverberate across continents and decades.

Also by Pam Jenoff

THE AMBASSADOR’S DAUGHTER

THE DIPLOMAT’S WIFE

THE KOMMANDANT’S GIRL

PAM JENOFF

The

Winter

Guest

For Mom, who makes our lives better every single day.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Questions for Discussion

Excerpt

Prologue

New York, 2013

“They’re coming around again,” Cookie says in a hushed voice. “Knocking on doors and asking questions.” I do not answer, but nod as a tightness forms in my throat.

I settle into the worn floral chair and tilt my head back, studying the stucco ceiling, the plaster whipped into waves and points like a frothy meringue. Whoever said, “There’s no place like home” has obviously never been to the Westchester Senior Center. One hundred and forty cookie-cutter units over ten floors, each a six hundred and twenty square foot L-shape, interlocking like an enormous dill-scented honeycomb.

Despite my issue with the sameness, it isn’t an awful place to live. The food is fresh, if a little bland, with plenty of the fruit and vegetables I still do not take for granted, even after so many years. Outside there’s a courtyard with a fountain and walking paths along plush green lawns. And the staff, perhaps better paid than others who perform this type of dirty and patience-trying work, are not unkind.

Like the white-haired black woman who has just finished mopping the kitchen floor and is now rinsing her bucket in the bathtub. “Thank you, Cookie,” I say from my seat by the window as she turns off the water and wipes the tub dry. She should be in a place like this with someone caring for her, instead of cleaning for me.

Coming closer, Cookie points to my sturdy brown shoes by the bed. “Walking today?”

“Yes, I am.”

Cookie’s eyes flicker out the window to the gray November sky, darkening with the almost-promise of a storm. I walk almost every day down to the very edge of the path until one of the aides comes to coax me back. As I stroll beneath the timeless canopy of clouds, the noises of the highway and the planes overhead fade. I am no longer shuffling and bent, but a young woman striding upward through the woods, surrounded by those who once walked with me.

And I keep a set of shoes by the bed all of the time, even when snow or rain forces me to stay indoors. Some habits die hard. “How’s Luis?” I ask, shifting topics.

At the mention of her twelve-year-old grandson, Cookie’s eyes widen. Most of the residents do not bother to learn the names of the ever-changing staff, much less their families’. She smiles with pride. As she raises a hand to her breast, the bracelet around her wrist jangles like ancient bones. “He made honor roll again. I’m about to go get him, actually, if you don’t need anything else...”

When she has gone, I look around the apartment at the bland white walls, the venetian blinds a shade yellower with age. Not bad, but not home. Home was a brownstone in Park Slope, bought before the neighborhood had grown trendy. It had interesting cracks in the ceiling, and walls so close I could touch both sides of our bedroom if I stretched my arms straight out. But there had been stairs, narrow and steep, and when my old-lady hips could no longer manage the climb, I knew it was time to go. Kari and Scott invited me to move into their Chappaqua house; they certainly have the room. But I refused—even a place like this is better than being a burden.

I look across the parkway at a strip mall now past its prime and half-vacant, wondering how to spend the day. The rest of my life rushed by in an instant, but time stretches here, demanding to be filled. There are activities, if one is inclined, knitting and Yiddish and aqua fitness and day trips to see shows. But I prefer to keep my own company. Even back then, I never minded the silence.

One drop, then another, comes from the kitchen faucet that Cookie did not manage to shut. I stand with effort, grimacing at the dull pain that shoots through my thigh, the wound that has never quite healed properly over more than a half century. It hurts more intensely now that the days have grown shorter and chilled.

Outside a siren wails and grows closer, coming for someone here. I cringe. Now, it is not death I fear; each of us will get there soon enough. But the sound takes me back to earlier times, when sirens meant only danger and saving ourselves mattered.

As I start across the room, I catch a glimpse of my reflection in the mirror. My hair has migrated to that short curly style all women my age seem to wear, a fuzzy white football helmet. Ruth would have resisted, I’m sure, keeping hers long and flowing. I smile at the thought. Beauty was always her thing. It was never mine, and certainly not now, though I’m comfortable in my skin in a way that I lacked in my younger years, as if released from an expectation I could never meet. I did feel beautiful once. My eyes travel to the lone photograph on the windowsill of a young man in a crisp army uniform, his dark hair short and expression earnest. It is the only picture I have from that time. But the faces of the others are as fresh in my mind, as though I had seen them yesterday.

A knock at the door jars me from my thoughts. The staff has keys but they do not just walk in, an attempt to maintain the deteriorating charade of autonomy. I’m not expecting anyone, though, and it is too early for lunch. Perhaps Cookie forgot something.

I make my way to the door and look through the peephole, another habit that has never left me. Outside stand a young woman and a uniformed policeman. My stomach tightens. Once the police only meant trouble. But they cannot hurt me here. Do they

mean to bring me bad news?

I open the door a few inches. “Yes?”

“Mrs. Nowak?” the policeman asks.

The name slaps me across the cheek like a cold cloth. “No,” I blurt.

“Your maiden name was Nowak, wasn’t it?” the woman presses gently. I try to place how old she might be. Her low, dishwater ponytail is girlish, but there are faint lines at the corners of her eyes, suggesting years behind her. There is a kind of guardedness that I recognize from myself, a haunted look that says she has known grief.

“Yes,” I say finally. There is no reason to hide who I am anymore, nothing that anyone can take from me.

“And you’re from a village in southern Poland called...Biekowice?”

“Biekowice,” I repeat, reflexively correcting her pronunciation so one can hear the short e at the end. The word is as familiar as my own name, though I have not uttered it in decades.

I study the woman’s nondescript navy pantsuit, trying to discern what she might do for a living, why she is asking me about a village half a world away that few people ever heard of in the first place. But no one dresses like what they are anymore, the doctors eschewing white coats, other professionals shedding their suits for something called “business casual.” Is she a writer perhaps, or one of the filmmakers Cookie referenced? Documentary crews and journalists are not an uncommon site in the lobby and hallways. They come for the stories, picking through our memories like rats through the rubble, trying to find a few morsels in the refuse before the rain washes it all away.

No one has ever come to see me, though, and I have never minded or volunteered. They simply do not know who I am. Mine is not the story of the ghettos and the camps, but of a small village in the hills, a chapel in the darkness of the night. I should write it down, I suppose. The younger ones do not remember, and when I am gone there will be no one else. The history and those who lived it will disappear with the wind. But I cannot. It is not that the memories are too painful—I live them over and over each night, a perennial film in my mind. But I cannot find the words to do justice to the people that lived, and the things that had transpired among us.

No, the filmmakers do not come for me—and they do not bring police escorts.

The woman clears her throat. “So Biekowice—you know of it?”

Every step and path, I want to say. “Yes. Why?” I summon up the courage to ask, half suspecting as I do so that I might not want to know the answer. My accent, buried years ago, seems to have suddenly returned.

“Bones,” the policeman interjects.

“I’m sorry...” Though I am uncertain what he means, I grasp the door frame, suddenly light-headed.

The woman shoots the policeman a look, as though she wishes he had not spoken. Then, acknowledging it is too late to turn back, she nods. “Some human bones have been found at a development site near Biekowice,” she says. “And we think you might know something about them.”

1

Poland, 1940

The low rumbling did not rouse Helena from her sleep. She had been dreaming of makowiec, the poppy seed rolls Mama used to make, thick and warm with a dusting of sugar. So when the noise grew louder, intruding on her dream and causing her hands to tremble, she clung tighter to the bread, drawing it hurriedly to her mouth. But before she could take a bite, a crash rattled the house and a dish in the kitchen fell and shattered.

She sat bolt upright, trying to see through the darkness. “Ruth!” Helena shook her sister. Ruth, who was curled up in a warm ball with her arms wrapped around the three slumbering children between them, had always slept more soundly. “Bombs!” Immediately awake, Ruth leaped up and grabbed one of their younger sisters under each arm. Helena followed, tugging a groggy Michal by the hand, and they raced toward the cellar as they had rehearsed dozens of times, not bothering to stop for the shoes lined up at the foot of the bed.

Helena scrambled down the ladder first, followed by Michal. Then Ruth passed five-year-old Dorie below before climbing down herself, the baby wrapped around her neck. Helena dropped to the ground and pulled Dorie onto her lap, smelling the sour milk on the child’s breath. She cringed as the inevitable wetness of the muddy earth seeped through her nightclothes, then braced herself for the next explosion. She recalled the horrors she’d heard of the Warsaw bombings and hoped that the cottage could withstand it.

“Is it a storm?” Dorie asked, her voice hushed with apprehension.

“Nie, kochana.” The child’s body relaxed palpably in Helena’s arms. Dorie could not imagine something worse than a storm. If only it were that simple.

Beside her, Ruth trembled. “Jeste´s pewna?” Are you certain there were bombs?

Helena nodded, then realized Ruth could not see her. “Tak.” Ruth would not second-guess her. The sisters trusted each other implicitly and Ruth deferred to her where their safety was concerned. Michal leaned his tangle of curls against her shoulder and she hugged him tightly, feeling his ribs protrude beneath his skin. Twelve years old, he seemed to grow taller every day and their meager rations simply couldn’t keep up.

Ten minutes passed, then twenty, without further noise. “I guess it’s over,” Helena said, feeling foolish.

“Not bombs, then.”

Helena could sense her sister’s lips curling in the darkness. “No.” She waited for Ruth’s rebuke for having dragged them needlessly from bed. When it did not come, Helena stood and helped Dorie up the ladder. Together they all climbed back into the bed that had once belonged to their parents.

Helena thought of the noises early the next morning as she made her way up the tree-covered hill that rose before their house. The early-December air was crisp, the sky heavy with foreboding of the harsher weather that would soon come. It had not been her imagination—she was sure of that. She had heard the drone of the airplane flying too low and the sound that followed had been an explosion. But she could see for miles from this vantage point, and when she peered back over her shoulder, the tiny town and rolling countryside were untouched, the faded rooftops and brown late-autumn brush she had known all her life showing no signs of damage.

She was halfway up the hill when a rooster crowed. Helena smiled smugly, as though she had outplayed the animal at its own game. Pausing, she turned and scanned the horizon again, gazing out at the rolling Małopolska hills. Beyond them to the south sat the High Tatras, their snowcapped peaks obscured by mist. She gazed up at the half crescent moon that lingered against the pale early-morning sky. The wind blew then and the moon seemed to duck behind some silvery gray clouds, casting light around the edges.

Helena bent to untangle the frayed hem of her skirt from the tops of her boots with annoyance. Her eyes dropped once more. Biekowice was just one of a dozen or so villages surrounding the larger town of My´slenice, spokes on a wheel fanning across the countryside. The entire region had been part of the Austrian empire not thirty years earlier and the latticed, red roof houses still gave it a slightly Germanic feel. There was one road into town, feeding into a cluster of streets, which wound claustrophobically around the market square like a noose. Another road led out just as quickly. A patchwork of farms dotted the outskirts, gray smoke wafting from their chimneys to form a halo above.

Shifting the small satchel she carried, Helena continued along the western path, a pebble-strewn route that climbed upward toward the main road. In the stream that ran alongside the path, water gurgled. Her footsteps fell into an easy rhythm. Despite her mother’s admonitions, Helena had escaped to the woods frequently as a child. In the confines of their small cottage, she bounced about restlessly like a rubber ball, with nowhere for her energy to go. But this was the one place she could be by herself and truly feel free.

Pine needles crackled beneath her feet, breaking the stillness, their scent mixing with more than a hint of smoke. What brush or refuse could the farmers be burning now?

Everything, even items once discarded, might have some use. Leaves and twigs could, if not fuel a fire, at least make it burn longer, stretch the logs or make them hotter when the wood in the pile was damp. She scoured the ground now as she walked, looking for dropped berries or nuts or even acorns that might be used for tea. But the earth here was picked bare by the animals, as ravenous and desperate as she.

The war had broken out more than fifteen months earlier, and for a while, despite the warnings that crackled nonstop across the radio, first in Polish and later in German, it seemed as though it might not have happened at all. Though their small village was less than twenty kilometers from Kraków, little had changed other than the occasional passing of military trucks on the high road outside town. It was the blessing, Helena reflected, of living in a place so sleepy as to be of no strategic value. But the hardships had come, if not the Germans themselves: herds of cattle and other livestock disappeared in the night, reportedly over the western border. Coal stores were requisitioned and sent to the front to help the war effort. And an unusually cruel summer drought had contributed to the misery, leaving little to be canned for winter storage.

She reached the paved road that led toward the city. It was deserted now, but exhaust hung freshly in the air, suggesting a car or wagon had passed recently. Helena’s skin prickled. She could not afford to encounter anyone now. She looked longingly back toward the trees, but taking the steep, winding forest path would only slow her down.

As she started forward, Helena’s thoughts turned to the previous evening. “Don’t go,” Ruth had begged as they readied the children for bed. They’d worked seamlessly in tandem as they’d completed the familiar grooming chores, like two appendages of the same body. “It’s dangerous.” She accidentally pulled Dorie’s braid too hard, causing her to squeal.

Ruth’s objection was familiar. She had fought Helena since she’d first proposed going to the city, continuing Tata’s weekly pilgrimage after his death. It was not so much that the half-day trek was physically demanding; Helena had navigated the steep, rocky countryside with her father all her life. But the Nazis had forbidden Poles from traveling beyond the borders of their own provinces without work passes. If they noticed Helena and asked questions, she could be arrested.

The Orphan's Tale

The Orphan's Tale The Lost Girls of Paris

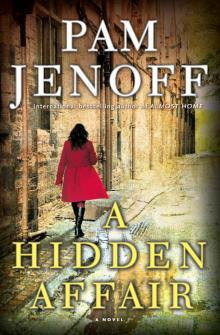

The Lost Girls of Paris A Hidden Affair: A Novel

A Hidden Affair: A Novel The Last Embrace

The Last Embrace Almost Home: A Novel

Almost Home: A Novel A Hidden Affair

A Hidden Affair Almost Home

Almost Home The Winter Guest

The Winter Guest The Last Summer at Chelsea Beach

The Last Summer at Chelsea Beach The Ambassador's Daughter

The Ambassador's Daughter The Things We Cherished

The Things We Cherished The Diplomat's Wife

The Diplomat's Wife The Kommandant's Girl

The Kommandant's Girl The Other Girl

The Other Girl